COP16 Dispatch: Day 1 Ecocide Law as Enforceable Protection for Biodiversity: How Businesses and Civil Society Can Support State Leadership

By Claire Bandet

Introduction

Earlier this year, Vanuatu, Fiji, and Samoa jointly introduced “ecocide” as a crime to be considered by the International Criminal Court. This meeting’s goal was to discuss the theoretical and practical framework of ecocide laws and to educate participants about their potential. The panelists were: Jojo Mehta, Stop Ecocide International; Aresio Valiente Lopez, University of Panama; and Sophie Demenski, Ecosia UK. The following is a summary of the discussion.

Definition of Ecocide

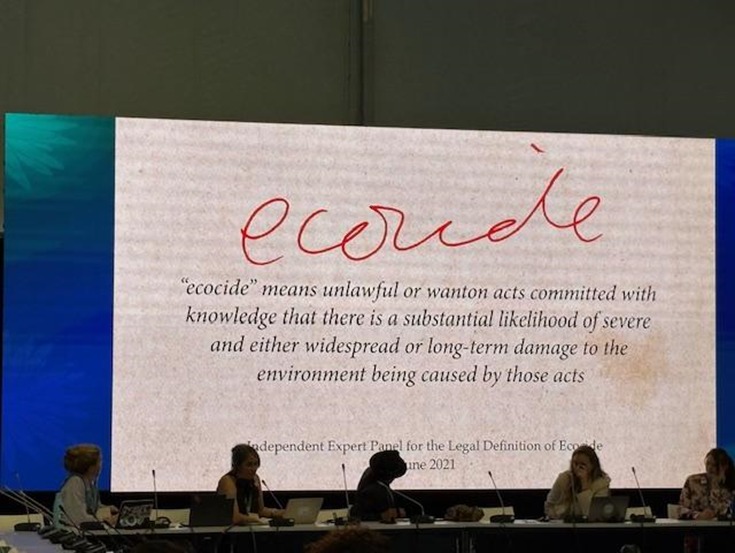

“Unlawful or wanton acts committed with knowledge that there is a substantial likelihood of severe and either widespread or long-term damage to the environment being caused by those acts” –Independent Expert Panel for the Legal Definition of Ecocide (June 2021).

A theoretical framework: criminal law vs. regulatory law

Environmental laws exist, but most are regulatory in nature. This means that they are not stigmatized to break and that it is often cheaper to pay for breaching regulation than to comply. Ecocide laws, ecocide terminology, ameliorates those issues. They serve as a safety rail, setting an outer limit on the worst behavior by creating enforceable, personal consequences. The key deterrent against allowing environmental destruction becomes the personal desire to avoid criminal liability on behalf of the most powerful (the CEOs), which is a much more powerful deterrent than relatively small financial penalties felt by the company, on the grounds that it is more personal.

With regard for the need for ecocide laws as well as regulation, there was also some criticism of neoliberalism, and the idea that the free market will yield the best result. A series of questions were posed: What is freedom? Is free market choice between consumer goods true freedom when the production of those goods is predicated on ecocide? When the production impinges on the freedoms of individual others, other communities, and common resources?

Public opinion and precedent

A survey of public opinion (source uncaught by this author) showed widespread support for these laws, and that legal discussion and precedent are robust. This was emphasized since the panelists claim both those aspects are needed for politicians and policy makers to propose and pass the laws. They encouraged audience members to introduce ecocide as an idea in their own dialogs as an impactful way of furthering their adoption.

Criminal laws with regard to what is considered business practices do have some precedent, both within the regulated community and without. Ecosia, Patagonia, Oatly, and Tony’s Chocolonely were cited as companies who recently came together to urge the EU to adopt an ecocide law, showing that there is precedent for businesses who advocate for regulation within their sector. Criminal laws regulating the financial system were cited as an example of criminal law being used to more effectively incentivise businesses to perform up to a socially acceptable standard than regulatory law; thus, ecocide laws can and should be created to bring environmental crimes into line with social standards.

Matters of practicality

Criminal law is cheap, quick to enact, and a very strong deterrent—particularly in the business sphere. CEOs are generally rational actors, so the creation of criminal ecocide laws can be particularly effective. Ecocide is consequence focused, where regulation is activity focused. When regulation sets specific limits for actions like effluent release, the regulated community very reasonably argues that regulations are too complicated, and regulation allows for and even rewards gamifying the effort to circumvent. Criminal law changes the paradigm from action oriented to impact oriented. It is concerned with safety, so businesses and their CEOs would have to consider the criminal impact of their actions (and the resulting personal consequences) rather than or in addition to simply the legality of their actions in the eyes of a regulatory body.

During the question period, the speakers note that ecocide laws are mostly a deterrent in peacetime but acknowledge that significant ecocide is caused by conflict. As one of the audience members brought up, 86,000 bombs have been detonated in Gaza

in the last year, resulting in 281,000 tons of CO2 being released into the atmosphere, the destruction of Gaza’s waste management systems, and significant air and noise pollution. Ecocide laws are not sufficiently deterrent to prevent conflict at this scale, but the panelists point out that they could be used after the fact to hold perpetrators to account and prosecute humanitarian efforts through an ecocide lens.

Defining Ecocide at a COP16 Presentation

Disclaimer: Opinions are solely those of the guest contributer and not an official ESA policy or position.