Out of the ashes: The Gulf, one year later

Last year the world’s eyes turned to the Gulf of Mexico when British Petroleum’s Deepwater Horizon drilling unit exploded, causing what became the largest accidental marine oil spill in the history of the petroleum industry. Eleven people lost their lives in the explosion that resulted in 205.8 million gallons of crude oil leaking into the Gulf, 17 were injured, and countless more had to rebuild their livelihoods.

Last year the world’s eyes turned to the Gulf of Mexico when British Petroleum’s Deepwater Horizon drilling unit exploded, causing what became the largest accidental marine oil spill in the history of the petroleum industry. Eleven people lost their lives in the explosion that resulted in 205.8 million gallons of crude oil leaking into the Gulf, 17 were injured, and countless more had to rebuild their livelihoods.

This time last year Deepwater Horizon was still spewing about 53,000 barrels per day into the Gulf, in a community still recovering from 2005’s Hurricane Katrina. This year, Gulf residents are bracing themselves for another assault—one that arrives every summer.

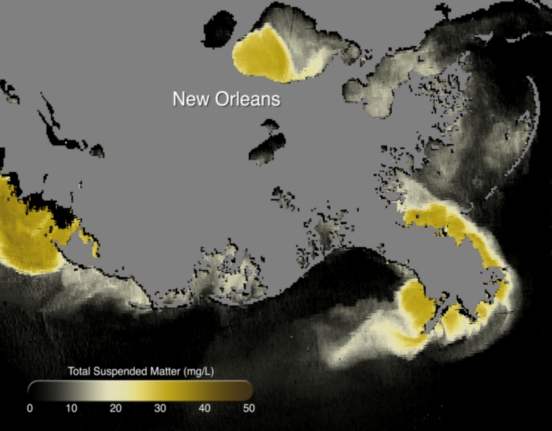

That is, the Mississippi River deposits nutrients into the coastal waters of the Gulf of Mexico. The influx of nutrients sets off a chain reaction that transforms a large area of the Gulf into a massive “dead zone” where virtually no aquatic organism can survive. This area, off the Gulf coast of Louisiana and Texas is the largest hypoxic zone currently impacting the United States, and it is second worldwide only to the Baltic Sea. Moreover, this year’s is predicted to be the biggest ever due to excessive flooding (see the above image showing sediment from the Mississippi River). The Gulf just can’t seem to get a break. So where does the problem start?

When it rains, it pours. Rain that falls almost anywhere between the Rocky Mountains in the West and the Appalachian Mountains in the East (about 40% of the land area of the lower 48 states), with some exceptions, drains into the Mississippi. The majority of the land in this area is farmland, and the majority of farms in the Midwest are dependent on chemical fertilizers. “As agricultural commodity prices have plummeted and farm communities continue to decline,” according to a factsheet published by the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy, “many farmers feel they have no choice but to intensively fertilize and maximize production of a few low-value commodities.” This winter and spring brought record snowfall and record amounts of precipitation to the central US, causing the Mississippi River floods of this spring. And big floods carry large amounts of fertilizer. Mississippi’s 1.2 million square mile watershed essentially funnels agricultural fertilizer straight into the Gulf.

If you’ve ever wondered why nutrients could be so bad for marine ecosystems, hypoxia, which means oxygen depletion, is your answer. Nutrients from chemical fertilizers feed giant algae blooms, which in turn feed a population boom in algae-eating zooplankton. Dead algae and zooplankton fecal pellets sink down to the sea floor and are feasted on by bacteria, a process that consumes oxygen. In the Gulf, this oxygen-depleted bottom layer of water is cut off from the atmosphere by fresh water from the Mississippi, which is seasonally warm and therefore less dense. This water stratification prevents the bottom layer from replenishing lost oxygen, and eventually the concentration of dissolved oxygen in the water column reaches a point that can no longer support living aquatic organisms.

The Gulf’s dead zone isn’t just bad for ecosystems; it also takes a huge toll on human residents of the Gulf coast. The most delicious of aquatic organisms affected by hypoxia are shrimp, oysters, crabs and finfish: seafood that support the $2.8 billion-per-year fishing industry in Texas and Louisiana. Moreover, hypoxia can cause fish kills (read: smelly dead fish on the beach), which can harm the $20 billion tourist industry.

Hurricanes and/or cold fronts in the fall and winter mix ocean waters and bring oxygen back to waters affected by hypoxia, ending the months-long dead zone and re-energizing Gulf coast fisheries. However, research has shown that seasonal hypoxic episodes seem to have cumulative effects. Because hypoxia in the Gulf occurs near shore areas, nursery habitat for fish and shellfish is often affected, which reduces the amount of aquatic youngsters reaching adulthood. This destabilizes economically important fish stocks. One study estimates that up to 25 percent of habitat for brown shrimp on the Louisiana shelf, the commercial fishing industry’s most valuable fish stock, is lost to the cumulative effect of annual hypoxia events. Hypoxic episodes also make the region generally less stable and more likely to be adversely affected by stressors like overfishing, pest outbreaks and catastrophes such as last year’s oil spill and 2005’s Hurricane Katrina.

Exacerbating the problem is the dire state of Gulf wetland areas. Wetlands provide a host of ecosystem services that play a key role in upholding the resiliency of Gulf ecosystems and communities. They promote denitrification—the conversion of nitrate (which is found in chemical fertilizers) into atmospheric nitrogen; wetlands also stave off erosion and purify groundwater by filtering out sediment. Wetlands and barrier islands buffer inland communities from floodwaters during storms and serve as a crucial wildlife habitat. About 95% of the Gulf’s wildlife relies on wetlands for survival at some point in their lifecycle.

But due to the combined forces of canal digging, oil and gas development, rising sea levels, levees and a large invasive rodent with a strong appetite for marsh plants, more than 4,000 square kilometers of marshland on the Gulf coast have been lost since 1950. Even before Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, in the two decades before 2005 Louisiana’s coast wetlands were already losing about 10-14 square miles a year. If Gulf coast wetlands were in better shape, the effects of seasonal hypoxia events and unpredictable catastrophes like Deepwater Horizon and Katrina might not be so severe.

Take a history of degradation, add annual hypoxic events to the mix, and season it with a sprinkling of disastrous one-time events, and you have the state of the Gulf coast. Moreover, Deepwater Horizon continues to present a threat to Gulf communities, as no one really knows what the long-term effects might include. But, ironically, the most recent insult to the Gulf coast may also prov ide some silver lining. Donald Boesch at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, and a member of the National Oil Spill Commission has a somewhat positive outlook. As he mentioned in a recent Smithsonian Institution event entitled “The Gulf and Its Seafood – One Year Later,” he hopes that a comprehensive restoration of the Gulf will rise from the ashes of the spill. That is, attention and resources initially geared toward the oil spill could also be directed to help address other environmental issues in the Gulf.

ide some silver lining. Donald Boesch at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, and a member of the National Oil Spill Commission has a somewhat positive outlook. As he mentioned in a recent Smithsonian Institution event entitled “The Gulf and Its Seafood – One Year Later,” he hopes that a comprehensive restoration of the Gulf will rise from the ashes of the spill. That is, attention and resources initially geared toward the oil spill could also be directed to help address other environmental issues in the Gulf.

In addition, wetland and barrier island restoration is one of the top priorities of the Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Task Force, a group created by President Obama following the Deepwater Horizon spill. The task force, which includes representatives from all five Gulf coast states, prioritizes local stakeholder and public engagement in the process, as well as science-based solutions to the Gulf’s environmental problems. Task force members hope to identify and expand successful Gulf projects, including existing research on annual hypoxia episodes. And they hope to create the first holistic approach to restoration. The task force has to present the President with a report and a long-term strategy for restoring Gulf ecosystems this July.

Photo Credit (turbidity): NOAA

Photo Credit (Smithsonian panel on the Gulf; Donald Boesch, Ted Danson, Lucina Lampila, Patrick Riley, Mike Voisin and Jane Lubchenco pictured): Katie Kline