Science in a “culture of news-grazers”

When was the last time you sat down after dinner to watch the local news? How about the last time you forwarded or received a link to a news story? Odds are, with the prevalence of social networking, blogs and email, you probably sent or received news in some form during your lunch break this afternoon. In fact, just by reading this post you are providing evidence that consumers tend to prefer cherry picking news throughout the day, rather than replenishing their news supply all at once.

When was the last time you sat down after dinner to watch the local news? How about the last time you forwarded or received a link to a news story? Odds are, with the prevalence of social networking, blogs and email, you probably sent or received news in some form during your lunch break this afternoon. In fact, just by reading this post you are providing evidence that consumers tend to prefer cherry picking news throughout the day, rather than replenishing their news supply all at once.

This is the cultural news shift that Tom Rosenstiel—journalist and director of the Project for Excellence in Journalism, part of the Pew Research Center –described in a recent Media and Climate Change briefing in Washington, D.C. hosted last week by the American Meteorological Society. According to Rosenstiel, 56 percent of Americans get news both online and offline daily, with a vast majority gathering news from four to five platforms per day. In other words, you might watch the evening news, but it is probably supplemental to the links a friend posted on Facebook or a colleague forwarded to you at work—not to mention the handful of stories you searched for during your lunch break.

“We have become a culture of news-grazers,” he said, “we consume news throughout the day.” Rosenstiel suggested that Americans are increasingly gathering information at the story level instead of the news level; that is, they are actively seeking out specific topics that interest them as opposed to waiting around for the news to be provided to them “serendipitous[ly]” in the evening news.

Rosenstiel described this phenomenon as a “news ecosystem” where information is more readily available, surrounding the reader at all times and influencing other stories. Therefore, consumers are “functioning less as an audience and more as our own editors,” he said. With the wealth of information on the internet, it is the responsibility of the reader to determine if it is accurate, complete and reliable. Budget cuts and the decline of the newspaper industry are leading to a greater number of freelance journalists and less institutionalized reporting as well, said Rosenstiel. Blogging and social networking are on the rise as an inexpensive alternative.

“This is the landscape in which we live,” Rosenstiel said. “There is less reportorial news and more opinion news.” With the overload of information, the news culture may be evolving to rely more heavily on the consumers to be their own experts. Similarly, friends and coworkers may become more credible sources of information than a trusted news source. As Rosenstiel put it, “We’ve gone from the ‘trust me’ era of journalism to the ‘show me’ era.”

So what does this evolution into a culture of news-grazers mean for science? Ultimately, it may mean consumers will have to reach beyond relying on one credible source of information and may have to learn the basics of data analysis. Society may need to adapt in conjunction with the environment of science-infused information.

Bud Ward, a freelance environmental journalist who also spoke at the briefing, said scientists, journalists and readers all need to reevaluate their roles. He suggested that scientists should adopt some of the best practices of the best journalists, the media should study the work of the best scientists and science communicators and the consumers should be adept in both areas. The key to accurately reporting science, he said, is communicating the uncertainties. But that requires that consumers step up as well and critically assess the information they are inundated with daily.

Perhaps, then, the question to ask regarding this culture of news-grazers becomes, “Is society ready to learn the fundamentals of science?” That is, if a majority of American consumers are cherry-picking the issues they believe matter the most, what is to say they will not choose to read a story they know will be slanted in favor of their views?

In a recent Special Issue of Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, Matthew Nisbet from American University and colleagues addressed the delicate balance between communicating science and engaging the public in environmental issues, climate change in particular. As they wrote in the article:

“[T]he instinct of scientists faced with slow and inadequate societal responses to looming environmental emergencies has been to bring an ever-increasing amount of technical information to the public. Consequently, scientists have worked in relative disciplinary isolation, entering into interdisciplinary partnerships only to amplify their own voices. This strategy assumes that the appropriate technical information, offered in the right place and at the right time, is sufficient to motivate people to take action. Various studies, as well as the historical inefficacy of this strategy, call this assumption into question. Nor are attempts to influence public opinion ‘from the top down’ likely to be effective.”

The authors offered that the basis of societal interactions needs to be overhauled in order to effectively communicate complex environmental issues. They write that “[b]uilding societal action in response to climate change will require a new communication infrastructure, in which the public is empowered to learn about both the scientific and social dimensions of climate change, inspired to take personal responsibility, able to constructively deliberate and meaningfully participate and [be] emotionally and creatively engaged in personal change and collective action.”

In other words, communicators and journalists should consider established beliefs, cultural values and worldviews when communicating science. The message should come from religious and social groups, scientific organizations, academia and several types of media platforms “so that communication efforts about climate change [for example] become more diverse, more personal, more interactive, more compelling and more participatory,” they said.

The age of news-grazing may indeed be a “perfect storm,” as Ward put it, for advancing climate change, and other environmental messages. Complex, science-infused topics should probably be addressed from many angles to account for the diversity of opinions and beliefs of the public. And social networking platforms in particular may provide the versatility and accessibility needed to keep consumers engaged in dynamic environmental issues, such as climate change and environmental stewardship. Something to think about the next time you “Like” a link on Facebook and potentially add credibility to the topic.

For additional reading on the evolution of science communication, read the recent Special Issue of Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment.

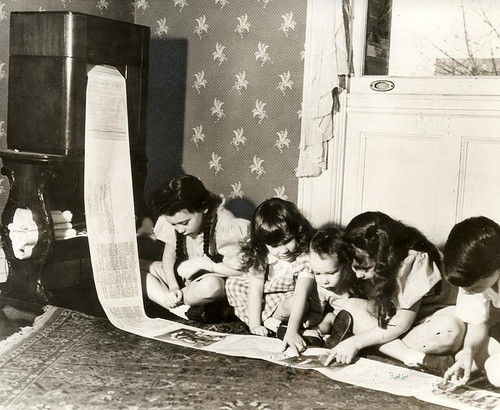

Photo Credit: Collectie Spaarnestad