Every week was Sharksucker Week for these bull sharks, until some trendsetting trevallies came along

Photos and video footage shows sharksuckers causing injuries, but also getting eaten

August 20, 2020

For Immediate Release

Contact: Heidi Swanson, (202) 833-8773 ext. 211, gro.asenull@idieh

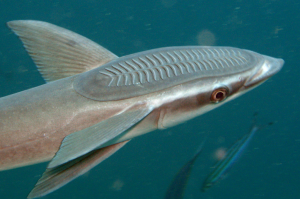

Adhesive disc of a sharksucker (Echeneis naucrates) in Beqa Lagoon, Fiji. Photo courtesy of Richard Ling; CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Textbooks and encyclopedias typically describe the sharksucker – whose bizarre head accoutrements allow it to latch on to various marine predators – as a harmless, if not helpful sidekick. A paper published this week in the Ecological Society of America’s journal Ecology offers observations of sharksuckers that challenge this portrayal.

Lead author Juerg Brunnschweiler and his colleagues have been watching sharksuckers for years, mainly in Fiji’s Shark Reef Marine Reserve, where they hand-feed bull sharks (Carcharhinus leucas). In the video footage that accompanies the paper, a shark charges towards the diver, getting impossibly close before chowing down on the severed tuna head dangling from the feeder’s hand. Taking a closer look, however, a more complex scene emerges.

Just behind the shark’s gill opening, a fish clings to the shark’s side. The fish is a sharksucker (Echeneis naucrates), commonly known as remora – an unabashed freeloader whose head sports a flat adhesive disc, roughly resembling the tractioned sole of a shoe, that can attach to sharks and other large marine animals. Free rides and free food are just two of the ways that sharksuckers benefit from their association with large roving predators.

For the sharksuckers’ hosts, however, the benefits are less clear. In 2013, Brunnschweiler and colleagues noticed a sharksucker clinging to the same blubberlip snapper almost every time they dived at a particular site, and the sharksucker always latched on to the exact same spot on the snapper’s side. The snapper developed a large sore that only healed when the persistent remora finally abandoned ship – after an entire year of damaging devotion.

A sharksucker attached to blubberlip snapper in 2013 (left). Skin abrasion due to sharksucker

attachment (right). Photo courtesy of Juerg Brunnschweiler.

Witnessing these longer-term interactions is one of the advantages of visiting the same dive sites time and time again. “I have been involved with the Shark Reef Marine Reserve in Fiji from its very beginnings and have logged hundreds of dives there since 2002,” says Brunnschweiler, who does field work in Fiji and publishes his findings as an independent researcher – all in addition to his day job, a managerial position at ETH Zurich, the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology.

Brunnschweiler’s fascination with sharksuckers has been a mainstay throughout his career. “For my master thesis, I looked at the sharksucker–shark interaction, and was lucky enough to document some really spectacular behavior, like a blacktip shark jumping out of the water – presumably to get rid of sharksuckers,” he explains. “Once you start looking you can see some really cool stuff!”

Now, the authors suggest a new possible mechanism for banishing sharksuckers who have overstayed their welcome. Starting in 2011, the dive team began to observe giant trevallies (Caranx ignobilis) snapping up sharksuckers from bull sharks. But after a few months, the trevallies suddenly stopped eating sharksuckers. Brunnschweiler speculates that the short-lived practice was a behavioral innovation that began to spread through social learning, but that disappeared with population turnover.

If this is the true, then when the trevallies that had been the innovators and early adopters of sharksucker consumption disappeared, so would the new feeding practice. “To the best of my knowledge, Caranx ignobilis – or any other Caranx species – has not been documented to have adopted new behaviors as a result of social learning,” says Brunnschweiler. “Such a hypothesis will need to be tested with specific experiments with captive fish.”

Brunnschweiler acknowledges that it is hard to draw your eyes away from the spectacle of sharks, but emphasizes the complexity and mystery of the underwater world. “There are so many fascinating things and behaviors to detect and observe in the marine realm,” he says. “Once you start looking and paying attention to the little, or not so little, things, a rich world full of fascinating stuff opens up.”

Journal article:

Brunnschweiler, Juerg, et al. 2020. “The costs of cohabiting: the case of sharksuckers (Echeneis naucrates) and their hosts at shark provisioning sites.” doi.org/10.1002/ecy.3160

Authors:

Juerg M. Brunnschweiler1,5, Thomas M. Vignaud2, Isabelle M. Côté3. Aleksandra Maljković4

1Independent Researcher, Zurich, Switzerland; 2Independent Researcher, Grand Baie, Mauritius; 3Earth to Ocean Group, Department of Biological Sciences, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, Canada; 4Independent Researcher, Cheltenham, UK

Author contact:

Juerg Brunnschweiler (ten.hcilkceulgnull@greuj)

###

The Ecological Society of America, founded in 1915, is the world’s largest community of professional ecologists and a trusted source of ecological knowledge, committed to advancing the understanding of life on Earth. The 9,000 member Society publishes five journals and a membership bulletin and broadly shares ecological information through policy, media outreach, and education initiatives. The Society’s Annual Meeting attracts 4,000 attendees and features the most recent advances in ecological science. Visit the ESA website at https://ecologicalsocietyofamerica.org.