Rattlesnakes and ticks, competition and cannibalistic salamanders, and beneficial, predatory, parasitic Fungi

Presentations on species interactions figure large at ESA’s 2013 annual meeting

For immediate release: Monday, 29 July 2013

Contact: Nadine Lymn (202) 833-8773 x 205; gro.asenull@enidan

Viper tick removal service

Human cases of Lyme disease continue to rise in the United States. The bacterial disease—which, if untreated can cause significant neurological problems—is transmitted to people by black-legged ticks, which pick up the pathogen by feeding on infected animals, primarily small mammals such as mice.

Previous studies have shown that when fewer predators of small mammals are present, the abundance of ticks goes up, resulting in an increase of Lyme infections in people. Edward Kabay, at East Chapel Hill High School, together with Nicholas Caruso at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa and Karen Lips with the University of Maryland, explored how timber rattlesnakes (Crotalus horridus) might play a key role in the prevalence of Lyme disease in humans.

They modeled what and how much timber rattlesnakes ate based on published data on snake gut contents for four northeastern localities and determined the number of infected ticks removed from each location. Kabay, Caruso and Lips’ models showed that by eating mammalian prey, the snakes removed some 2,500 – 4,500 ticks from each site annually. Rattlesnakes eradicated more ticks in areas with greater prey diversity than in habitats with less mammalian diversity. The trio’s research suggests that top predators like the timber rattlesnake play an important role in regulating the incidence of Lyme disease. But decreasing habitat and overharvesting of the snakes is driving their populations down, particularly in northern and upper midwestern areas, where the incidence of Lyme disease is highest.

The presentation Timber Rattlesnakes may reduce incidence of Lyme disease in the Northeastern United States will take place on Tuesday, August 6, 2013: 4:40 PM in 101 I of the Minneapolis Convention Center.

Presenter contacts:

Edward Kabay, East Chapel Hill High School, moc.liamgnull@yabake

Nicolas Caruso, University of Alabama, ude.au.nosmircnull@osuracmn

Karen Lips, University of Maryland, ude.dmunull@spilk

Unexpected cannibals

Kyle McLean, an Environmental & Conservation Sciences graduate student at North Dakota State University, and his team looked at the two different types of juvenile barred tiger salamanders: the ‘typical’ variety and the rarer, cannibalistic morph. A morph occurs when the same species exhibits different physical characteristics. The cannibalistic morph is believed to be a result of plasticity; it’s changed its physical appearance due to environmental pressures. The typical morph has a smaller head and smaller peg-like teeth compared to the cannibalistic morph’s broader head and sharper recurved teeth, allowing the cannibalistic morph to eat larger prey and, in many cases, other salamanders of the same species. In water bodies where the morphs occur, they have been observed at less than 30 percent of the local population. McLean thinks cannibalistic morphs occur at the larval stage when competition for food is highest.

During the summer of 2012, McLean’s team collected 54 barred tiger salamanders (Ambystoma mavortium diaboli) from a North Dakota lake with a high concentration of fathead minnows that likely compete with larval salamanders for prey. The team measured the salamanders’ body length, skull, and teeth. They concluded that all were cannibalistic. Their snout length was not significantly different from that of typical barred tiger salamanders from a nearby lake, but the cannibalistic morphs had longer and wider skulls and larger, sharp teeth. Typical morphs came from a lake with a low abundance of competitors for food, possibly indicating that the cannibalistic morph occurs where there is a high concentration of predatory competition.

“The presence of cannibal morphs occurring in the barred tiger salamander was an unexpected discovery, but being that that every individual captured from the lake was a cannibal morph and they appear to not be in competition with each other but thousands of fathead minnows is the intriguing story, said McLean. “With future experimentation and data collection hopefully we will be able to better understand the abnormalities of this unique population.”

McLean’s poster session, Characteristics of cannibalistic morph barred tiger salamanders in a prairie pothole lake will take place on Wednesday, August 7, 20113 in Exhibit Hall B of the Minneapolis Convention Center.

Presenter contact:

Kyle McLean, North Dakota State University; ude.usdn.ymnull@naelcm.elyk

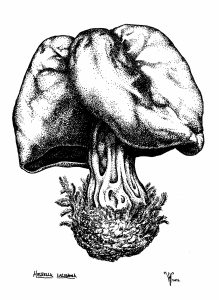

Slime, spores…fungi!

As different from plants as plants are from animals, Fungi feature varieties that decompose dead organisms, engage in mutually beneficial relationships with other species, cause disease to plants and animals, and act as predators and parasites. Mycologists—those who study fungi and their relationships with other organisms—note that only a fraction of Fungal species are known and that modern mycology’s potential applications to engineering and other possible contributions remain largely untapped.

Part of the organized poster session Current Perspectives on the History of Ecology, Getting freaky with fungi: A historical perspective on the emergence of mycology, will take place on Wednesday, August 7, 2013, from 4:30 – 6:30 PM in Exhibit Hall B of the Minneapolis Convention Center.

Presenter contacts:

Sydney Glassman, University of California, Berkeley, ude.yelekrebnull@namssalgs

Roo Vandegift, University of Oregon, ude.nogerounull@vwa

Media Attendance

The Ecological Society of America’s Annual Meeting, Aug. 4-9, 2013 in Minneapolis, Minnesota, is free for reporters with a recognized press card and institutional press officers. Registration is also waived for current members of the National Association of Science Writers, the Canadian Science Writers Association, the International Science Writers Association and the Society of Environmental Journalists. Interested press should contact Liza Lester at gro.asenull@retsell or 202-833-8773 x 211 to register. In a break from previous policy, meeting presentations are not embargoed.

The Ecological Society of America is the world’s largest community of professional ecologists and the trusted source of ecological knowledge. ESA is committed to advancing the understanding of life on Earth. The 10,000 member Society publishes five journals, convenes an annual scientific conference, and broadly shares ecological information through policy and media outreach and education initiatives. Visit the ESA website at https://ecologicalsocietyofamerica.org or find experts in ecological science at https://ecologicalsocietyofamerica.org/pao/rrt/.

To subscribe to ESA press releases, contact Liza Lester at llester@esa.org